Countless shaky videos, recorded at a height of perhaps 80 cm above the floor, document the family life of Prof. Dr. Manuel Bohn. You can see – almost as through the eyes of a toddler – how a child runs from one room of the flat to another, sometimes seeing its mum, sometimes its dad with the baby in his arms. Sometimes waddling around with a picture book in its hands, sometimes playing with its toys. Not the classic family records of a child growing up, but real, unedited everyday family life.

There is a reason why Bohn documents the everyday life of his family in such an unfiltered manner: he is not only the father of three children, now aged seven, five and three, but also a passionate developmental psychologist who has set himself the task of researching the connection between everyday experience and communication skills – across cultural boundaries. ‘And sometimes my own children have to act as human guinea pigs,’ he says with a grin.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from Youtube. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationA global view of developmental psychology: Manuel Bohn in a video portrait

ehrenwerk.tv für VolkswagenStiftung

As a methodologist, he tries to make psychological development more tangible: hard data and facts instead of assumptions and theories that are difficult to prove. Seemingly never satisfied with what may appear to be scientifically feasible, he looks for ways to find out what is typically human – and to weed out assumptions that perhaps only work for certain cultural groups. Because if you want to make generalisations, you have to broaden your view beyond your own culture and artificial experimental set-ups. ‘If we want developmental psychology to remain scientifically relevant, we need to put it on a more stable foundation,’ says Bohn.

A long way to the right specialization

This career path was not predetermined. Bohn’s younger self would probably even be surprised at his present occupation, as his interest in developmental psychology was awakened rather late. ‘As a child, I had a burning interest in history, especially antiquity,’ he says. As soon as he could read in primary school, he began to devour Greek legends. Later, medieval history was added as a centre of focus.

He has never completely let go of this area of interest. Even today, he still likes to pick up a book on a historical topic when he has the time. For example, on a train journey between Leipzig, where he lives with his family, and Lüneburg, where Bohn now holds a ‘Lower Saxony Impulse Professorship‘ at Leuphana University.

ehrenwerk.tv für VolkswagenStiftung

Since 2024, Bohn has headed the Developmental Psychology department at the Institute of Psychology in Education at Leuhpana University Lüneburg.

‘Maybe I just didn’t have the courage to become a historian,’ he says. ‘I thought it could be a bit too difficult to earn a living.’ After leaving school, he was also exposed to new influences and inspirations. Community service in psychiatry, for example. Encounters and exchanges with other travellers while journeying around the world for six months as a young man, not to forget the books on philosophy he read during this time – but also the experience of being cut off from his previous social environment. ‘You can feel quite lonely, even though you’re never actually alone,’ he recalls. ‘That made me realise how important the social environment is, and led me to the big question of how our environment makes us the people we are.’

From Vienna via New York to Leipzig

Bohn finally decided to study psychology and follow his girlfriend – now his wife – to Vienna. ‘Perhaps it was my good fortune that psychology in Vienna was very methodical at the time,’ says Bohn. The researchers there were looking for ways and means to make the human psyche – invisible mental states – tangible with the help of robust methods. ‘I found that cool and very inspiring.’

However, he couldn’t warm to developmental psychology at all. ‘It was the most boring subject I ever studied, an uninspired stringing together of different life stages,’ says the researcher – and has to laugh at himself.

Instead, he became interested in the evolutionary view of psychology and the really big question of what makes us human. But how should these questions be approached? During a semester abroad in New York, Bohn ventured into the field of neuroscience. But even there he didn’t find the answers he was looking for. ‘I began to realise that ultimately, a brain scan can only measure brain activity – it doesn’t capture what’s actually going on in the brain.’

ehrenwerk.tv für VolkswagenStiftung

The aim of Bohn's current research is not to come up with new theories. 'We have enough of that. We can finally check which of the existing theories are tenable and which are not.'

At first he had no luck when he entered the terms ‘evolutionary psychology’ and ‘Germany’ into his computer search engine in his small New York flat share room. Then a hit: the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig. ‘I was immediately fascinated by the fact that they actually do psychological research with apes. I hadn’t come across that in my studies,’ says Bohn. So here it was, the attempt to place humans and their characteristics in an evolutionary context using playful observational studies. ‘If we assume that the last common ancestor of apes and humans is somehow similar to the apes living today, then we can use comparative research to assess what makes us unique.’

Bohn applied for an internship and then went through what he describes as a typical career at the institute with his Diplom followed by a doctoral thesis. Among other things, during his time in Leipzig he worked on gesticulation as part of non-verbal human communication – an issue that clearly showed how important it is to conduct comparative research between different species in order to be able to draw the line between what is typically human and what is perhaps not.

Communication via gestures ‘typically human’

The experiment showed that when two human children are in contact with each other in a video call without sound, they very quickly begin to communicate using gestures. They imitate each other and develop a kind of common sign language. By means of gesturing, children as young as two to three years old are able to understand how to operate a piece of equipment, for example. ‘Monkeys can’t do that – at least not in my studies. No matter what I did, they largely ignored the iconic gestures.’

ehrenwerk.tv für VolkswagenStiftung

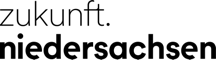

Bohn and his team designed colorful vests with a camera built into them for their study. It films the children's everyday lives from their perspective, while artificial intelligence helps to analyze the data.

This type of communication is therefore typically human. Why are humans able to do this while apes are not? Bohn prefers to leave this question to others. It is too speculative for him. Instead, he had another question to consider: How do we humans learn to do this? After all, we are not born with the ability to speak or communicate with the help of gestures. ‘That’s where developmental psychology comes into play – which I found so boring as a student,’ he says with a good dose of self-irony.

There are many theories on how language acquisition works. One common one is that language development requires direct interaction between parents and children, i.e. face-to-face communication: for example when parents point things out and name them. The quality and quantity of this interaction therefore determines how well language development progresses. That sounds logical enough. But can it really be generalised? ‘Not everywhere in the world do parents do what we do – and the children still learn to speak and communicate,’ says the researcher.

Leipzig or Cambridge not representative of the world

Manuel Bohn wouldn’t be Manuel Bohn if he didn’t start to question this seemingly trivial point. ‘If you assume that children’s development depends on their everyday experiences, it’s really quite sobering to realise how little we actually know about this everyday life and children’s experiences with their environment.’ Studies based on questionnaires or short observation sequences in the laboratory can only reflect the world of children’s lives and experiences to a limited extent. ‘The problem is also that the sample is very limited,’ says Bohn. ‘What we observe in children in Leipzig, Lüneburg or Cambridge is simply not representative of the world as it really is.’

ehrenwerk.tv für VolkswagenStiftung

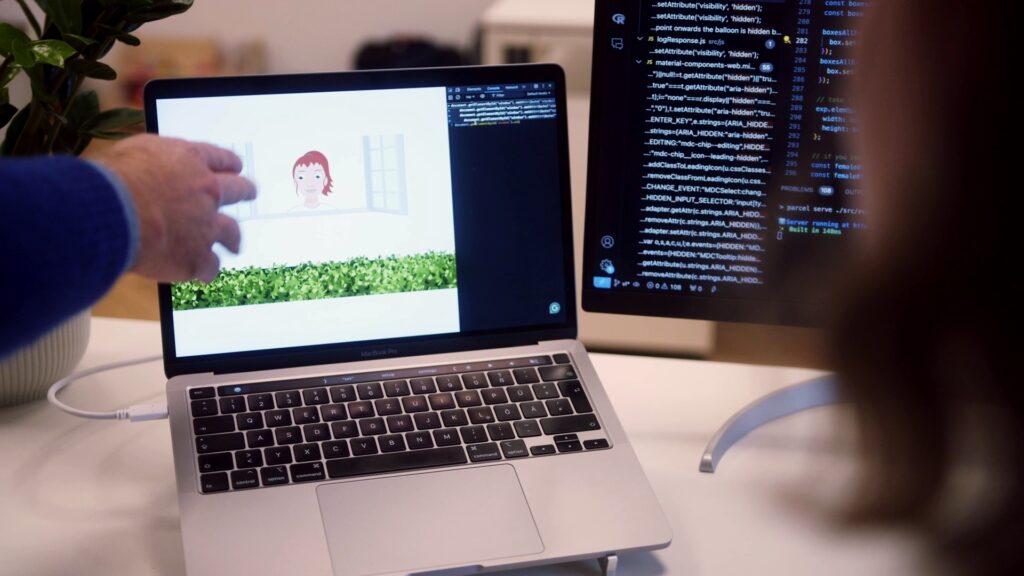

As part of the study, the everyday lives of 150 children aged between three and five in Germany, Kenya and Turkey were recorded on video. They will be followed for two years.

So how can data be collected from a realistic everyday life of children – and that across cultural boundaries? Together with his colleagues, Bohn developed waistcoats with a built-in camera that children can wear like a normal item of clothing. This enables their actual everyday life to be captured – in a quite matter-of-fact way . ‘This is where my own children came into play and I equipped them with the waistcoats to develop the method,’ says Bohn. Using the films, he and his team train computers to analyse the videos and use artificial intelligence to determine, for example, how many facial expressions the child actually sees in their everyday life. ‘This is quite challenging material, because the videos are not only long, but the images are also quite shaky and the children are constantly changing direction.’

International study for a better data basis

Bohn has adopted a pronounced international approach to developing the method and has trialled the waistcoats together with cooperation partners worldwide. ‘As part of the Lower Saxony Impulse Professorship, we can now start to apply this method in a large-scale international study and collect data that represents the realistic everyday experiences of children – across cultural boundaries,’ says Bohn.

‘This is a huge task and an equally huge opportunity!’ However, the aim is not to come up with new theories. ‘We have enough of those. We are, however, finally able to check which of the existing theories are tenable and which are not,’ says Bohn. ‘I think we can do a lot to put developmental psychology on a new, solid foundation to give it greater scientific relevance. In particular when it comes to making policy decisions.’